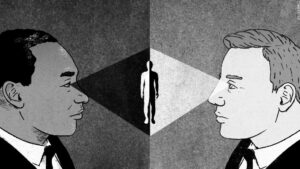

Stereotypes are an ever-present detriment to any community. Pre-judgments applied to already marginalized groups are backward strides in progression. The stone often left unturned is the way that stereotypes, specifically positive ones, often backfire in ways some people may not think about.

Think about what comes to mind when you think of the phrase “white people stuff.” What are “Caucasian activities” by definition? More importantly, what makes them exclusively Caucasian?

Commonly, Black people give these labels to things we find unappealing like mudding, walking around places barefoot, not using seasoning on foods, and not wearing a mask. Seemingly harmless, we often laugh these off. In an Instagram poll, I discovered people also include hiking, kayaking, camping and making casseroles in this category. In a Twitter thread of his very own “Caucasian activities,” Christopher Colonne pinned paddle-boarding as “the whitest date I’ve had.” None of these sound like outlandish things to do (besides the casseroles), so why are they exclusively white?

The dangers of these phrases enter when normalized activities, beneficial to any and all people, are labeled as things only white people do. For instance, the adult Black community is 20% more likely to experience serious mental health problems, according to Columbia University’s Department of Psychiatry. Despite that fact, one of the many stigmas keeping Black people from seeking psychotherapy is that it’s only for white people. Furthering this theory is the “strong Black woman” stereotype. As a Black woman, it feels good to be known as strong. However, once this stereotype is accepted, the factors that make it true — having to endure both racism and sexism with scarce social support — begin to seem like less of an issue. Whenever our “strength” seems to waiver or we voice our struggle, it’s dismissed as an overreaction.

“If we think Black women are strong, then there’s no reason to make the world more fair to them,” according to L’Heureux Lewis McCoy, a sociology and Black studies professor at City University of New York, interviewed by NPR in 2018.

When Black people rope off activities like those almost as a tease toward our white counterparts, we withhold them from ourselves. Unconsciously, we put ourselves in a box and limit the ways we have fun, what foods we eat, and ultimately how we live.

“You are what you think you are,” said Maurice Gilbert, a third-year political science and economics major at FAMU. “It can be limiting, I will admit.”

Many of these stigmas seem to have derived from slavery, and that makes sense. We tend to largely avoid being adventurous when it comes to water because slaves weren’t allowed to learn how to swim. Our apprehensiveness to explore nature more than likely stems from the trauma of running through the woods to freedom. The tragedies of our past are what birthed these stereotypes, but the subtle racism and micro-aggressions of today are what keep them alive.

The normality and accessibility white people have to all of their “Caucasian activities” versus the strange looks Black people would receive for doing the exact same thing reinforce the overarching theme of 2020: white people and Black people are living in two different Americas.