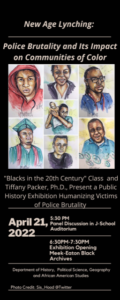

The auditorium in Florida A&M’s School of Journalism & Graphic Communication was packed Thursday as history professor Tiffany Packer and her African-American history to the 20th century class hosted a lively panel discussion prior to unveiling their new exhibition. Called “New age lynching: police brutality and its impact on communities of color, it opened at the Black Archives.

Students, alumni, professors, and community members were wall to wall as they listened closely to and interacted with the panel that included Shontae Day, Kiara Webb, Draper Miles, Marie Rattigan and Prof. Tiffany Packer.

Packer began the discussion by referencing an early Jay-Z track as she told the compelling origin story of the new age lynching project.

“I might date myself a little bit here, but to all my hip-hop heads I think you can rock with me: Do you remember Jay-Z’s song called “Song Cry’”? Just to remind those who might not, what he says is ‘I can’t let you see it coming down my eyes.’ So, we got to make the song cry,” she said.

Packer said this is exactly what happened to her on Sept. 14, 2013, when unarmed Jonathan Ferrell was murdered by police officers in Charlotte, N.C.

If the name Jonathan Ferrell sounds familiar to you, it should. Ferrell was a Tallahassee native and played football at FAMU. He had recently relocated to Charlotte to be with his fiancé, Cache Heidel, who was also born and raised in Tallahassee.

“After this happened, I tossed and turned for so many nights and when I went into the college classroom at Johnson C. Smith University [in Charlotte] where I was teaching a public history class at the time, my students’ faces were so long, everybody was so sad, droopy, and didn’t have much to say,” she said. So, I hit them with that Jay-Z song. I know why y’all are looking like that, but guess what, we about to make the work cry.”

Inspired by James Allen’s museum exhibition in 2000 titled, “Without Sanctuary,” Packer says that the vision for this collection is to rehumanize those who have been victimized by police brutality much like what Allen did as a photographer for late nineteenth and early twentieth-century America.

The discussion began to go off the rails a bit during the Q&A segment of the event when the unapologetic political science student, Amon McKinney, who is also a member of the Junior Reserves Officers Training Corps (JROTC) program and the Student Government Association (SGA), asked:

“What are your feelings toward those who share the belief that we cannot expect others to respect us when we don’t respect ourselves?”

Met with a hostile crowd accompanied by murmurs, sucked teeth, and deep, elongated breaths, Mckinney asked his question again.

After the audience had the chance to answer his question, student panelist and psychology student Draper Miles redirected him to focus on the issue at hand.

“As far as fixing everything in the Black community, it’s not going to happen all at once,” Miles said. “So, this specific panel tonight is about police brutality.”

“Racism is institutionalized and cannot be attacked all at once because there its more than one layer of it. Talking about Black-on-Black crime takes away from what we are trying to accomplish tonight.”

Marie Rattigan, who was also a panelist on Thursday night, concluded the discussion with powerful remarks.

“I’m telling y’all we got to get it together,” Rattigan said. “When I say get it together, I’m saying using our voice as a platform. You don’t have to be in the streets because we all have a seat in this movement. When we go to the Black Archives, it needs to be more people in there y’all that’s history. We have time for Set Friday, but we need to make time for history.”